East View Archive Editions

The Chinese Soviet Republic: Prototype for a Revolution

Coming Soon!

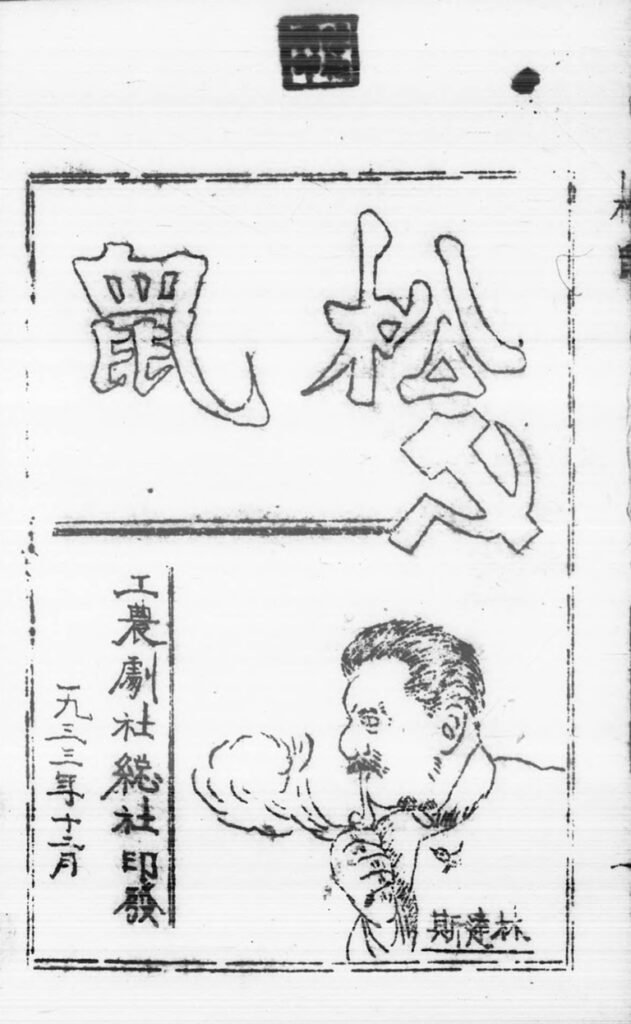

The Chinese Soviet Republic: Prototype for a Revolution is a collection of bulletins, letters, telegrams, and other documents originating from the Chinese Soviet Republic, a short-lived communist state founded by Mao Zedong and Zhu De on November 7, 1931, the fourteenth anniversary of Russia’s October Revolution.

Originally encompassing a narrow strip of land in the mountainous border region between Jiangxi and Hunan Provinces, the Chinese Soviet Republic (known in China as the Jiangxi-Fujian Soviet or, more officially, as the “Central Revolutionary Base”) rapidly expanded, eventually controlling an area of 27,000 square miles—roughly the size of South Carolina. Because the CSR had its own national bank, printed its own money, and collected its own taxes, this is considered the beginning of the Two Chinas.

The Chinese Soviet Republic was the largest portion of Republican China territory to operate under communist control until the 1949 establishment of the People’s Republic of China. As such, it was very much a “prototype” of what was to come. Led and inspired by Mao Zedong from 1931 to 1934, the Chinese Soviet Republic developed into a miniature model of fully functioning Communist society. This meant complete Communist Party control of the government, a Red Amy, a Party-led judiciary and educational system, and an economy that sustained this mini-state for years until it could no longer withstand its primary adversary, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army.

The sudden success of the CSR prompted Chiang Kai-shek to launch a series of military operations in the region with the goal of encircling and destroying it. These encirclement campaigns, known in official Chinese communist historiography as the Agrarian Revolutionary War. Facing annihilation, Mao was forced to end the experiment of the CSR and begin in late 1934 what became known as his Long March, a strategic retreat to sanctuary and survival in the north of China. But the lessons of running China’s first Communist State, and indeed in the establishment of “Two Chinas,” served Mao and his comrades well when their time came again in 1949.